In the Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula Le Guin compares two stories of human evolution, on the first cultural device of humanity. The first, the story of the spear, the bone, a big long hard thing, the weapon of the hunt, of conflict, heroism and domination, of violence inflicted on another for glory. This is always a didactic story, a very simple but exciting story. One that starts at one end and travels a straight line to the other, after a conflict, an enemy or an evil identified, a journey, a battle, and a conquering – a lesson is learned. This is a story that has been told again and again, in different forms. It is a story that is easy to tell and easy to grasp, and it is gripping. The story of the hero is a narrative that we see being represented heavily not only in cinema (see top grossing films of 2017)but also put into practice in the service of politics.

Who has heard the story of the axis of evil, that distant foreign enemy, which must be crushed in the war on terror? Or the story of that other oppressive foreign power, the European Union, costing us £350 million per week, stealing £650 million worth of fishing stock a year from UK fishermen, allowing immigrants to drain the resources of the NHS, of the economy. Those faceless immigrants who are stealing ‘our’ jobs, raping ‘our’ women, preventing ‘our’ country from the greatness and glory it once possessed. Who has heard this simple story, which starts and ends in fixed places, with one good hero, and one evil or untamed enemy, and one solution of conquering, or stamping out, or dominionism. Who has heard the story of Christopher Columbus. The story of the hero is his story, history, metanarratives of heroism and domination that have been shaped and told by those in power who would like you to believe that they are on your side and they, like you, for you, are facing new challenges, adversity to be overcome, whose answers are simple and whose solutions have no other, more complex causal factors, and perhaps ulterior motives.

The story of the hero, of the weapon, the spear, which starts in one place and travels a straight line to end in another, after a conflict, an enemy or an evil identified, is one we have heard over and over again. It is also the colonial, capitalist and patriarchal metanarrative that we are steeped in everyday, but it is also in places you would not expect. It is in feminism, which tells the story of the evil essential man who is the only enemy of the essential woman, who is her only oppressor and who even, disguised as a woman will try to infiltrate her spaces. It is in neoliberal leftism, which tells the story of the evil racist who lynches and uses racist slurs and wears a white hood, that faraway enemy ‘the racist’ who couldn’t possibly be present in the subtleties of your everyday behaviour within our white supremacist society, in your own white saviour (hero) complex, or in your own actions or inactions as non black people of colour. The story of the hero is digestible, unchallenging, and final. The story of the carrier bag is complex, unresolved, and ongoing.

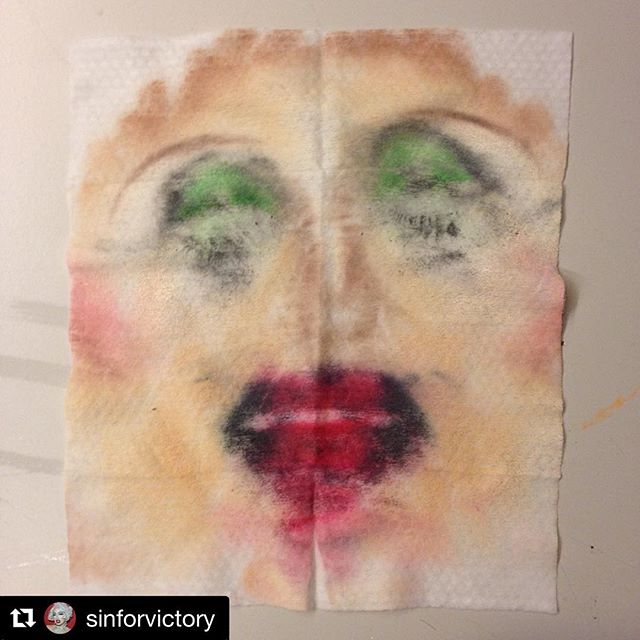

Victoria Sin (@sinforvictory) & Evan Ifekoya (@evan_ife) invite you to partake in a moment of queer collectivity, focusing on experiences of nightlife and the physical within the social body Thursday 9th September 7.30 – 8.30pm

In The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, the second, less told story of human evolution, of the first cultural device of humanity, is the carrier bag.

Before–once you think about it, surely long before–the weapon, a late, luxurious, superfluous tool; long before the useful knife and ax; right along with the indispensable whacker, grinder, and digger– for what’s the use of digging up a lot of potatoes if you have nothing to lug ones you can’t eat home in–with or before the tool that forces energy outward, we made the tool that brings energy home. It makes sense to me. I am an adherent of what Fisher calls the Carrier Bag Theory of human evolution.

The carrier bag is a device which does not go straight down, and identifies no common enemy, the carrier bag is a device which gathers many seeds, many stories, many individual parts which many not sit easily alongside one another, many perspectives perhaps, and holds them together for consideration. The story of the carrier bag is one which will hold you too, which will immerse you in a small or large sack containing another world, another social context, such as one which refigures ideas of ownership within society, or which offers up different models of gender and sex, and then asks what effects this would have on your way of being, and shows you a little what this would be like. This is the power of the narrative, of the novel, of the science fiction, of any serious fiction which seeks to describe a social reality, or image one which is hopeful, which is infinitely more powerful in its long term effects than that of the hero. This model of storytelling, of fabulation and speculation can be used as a representational strategy to refigure and reposition constructed notions of identity and society that hundreds of years of historical and scientific narratives have served to construct. We need carrier bag stories that complicate oversimplified narratives or gender, of race, of sexuality, of government, of punitive systems, of nature, of existing as an individual in a context with others within incredibly complex systems, which will problematize stories told by those in power, who control channels of information, who seek to simplify with misinformation, with stories and fictions of their own.

On the occasion of Ursula Le Guin’s passing, I am reminded of a short speech she gave receiving the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters at the 65th National Book Awards in 2014, speaking on the state of the publishing industry, and the importance of literature as something other than a market commodity.

I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope.

Four years later, hard times seem to be here. We are living in the dystopia imagined by Octavia Butler in 1993 in Parable of the Sower. Butler imagined an America after the verge of collapse, where a new leader has come into power through tactics of fear and paranoia and oversimplified narratives, who promises to “make America great again”, a sentence which encapsulates the story of a fallen hero, hard done by, whose easily identifiable enemies are the other, foreign bodies which must be stamped out, conquered.

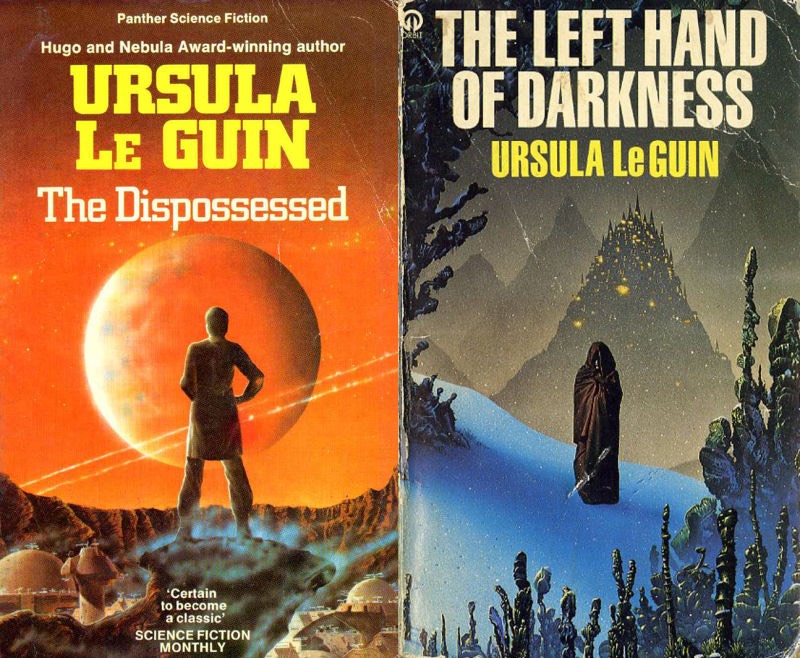

Carrier bag stories, such as Le Guin’s speculative fiction, are not just escapism, though happily, they do that too. In The Left Hand of Darkness, we are told the story of the planet Winter, whose people are completely without gender, sex, or sexuality for 21 or 22 days of the lunar cycle, but can occupy both a male or female sex for the remainder. The psychosocial effects of this are that burden and privilege are shared equally on Winter, and the society is not so divided into binaries of weak and strong, dominant and submissive, owner and property. After reading The Left Hand of Darkness, you return to life within our own social context with a slightly changed perspective, the effects of which are ongoing, and don’t sit easily, because they make us aware of work to be done. Carrier bag stories may carry us for awhile, they may give us a view from elsewhere and a sense of how things would feel in a different context, but they inevitably drop us back into the social context we are present in. However, finishing the story of The Left Hand of Darkness, I didn’t return unchanged, and I didn’t return empty handed. I returned with an image of a different social context, which while imperfect, was something which I could use to refigure my own attitudes towards gender and sexuality, and a hopeful sense of what it might feel like to live in a society undivided by the power structures of our sex-gender system.

Science fiction properly conceived, like all serious fiction, however funny, is a way of trying to describe what is in fact going on, what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.

Ursula Le Guin, thank you for your stories.

Sin Wai Kin (b. 1991, Toronto CA) is an artist using speculative fiction within performance, moving image, writing, and print to interrupt normative processes of desire, identification, and objectification. This includes:

Drag as a practice of purposeful embodiment questioning the reification and ascription of ideal images within technologies of representation and systems of looking,

Science fiction as a practice of rewriting patriarchal and colonial narratives naturalized by scientific and historical discourses on states of sexed, gendered and raced bodies,

Storytelling as a collective practice of centering marginalized experience, creating a multiplicity of social contexts to be immersed in and strive towards.

Drawing from close personal encounters of looking and wanting, their work presents heavily constructed fantasy narratives on the often unsettling experience of the physical within the social body.

Their long-term project Dream Babes explores science and speculative fiction as a productive strategy of queer resistance, imaging futurity that does not depend on existing historical and social infrastructure. It has included science fiction porn screenings and talks, a three-day programme of performance at Auto Italia, a publication, and a regular science fiction reading group for queer people of colour.