They ate nothing but leaves, says M. Not in person; through her website.

They ate nothing but leaves, she says through her website, in the voice of Margaret Atwood, 2004: 358, like she is doing a digital impression of Margaret Atwood, 2004: 358.

They ate nothing but leaves and grass and roots and a berry or two; thus their foods were plentiful and always available.

We walked to a small garden in Bermondsey, past a waste disposal site and a sewage works, over a railway line and past the home ground of Millwall Football Club. Red-brick, stacked maisonettes overshadowed the roundabout and deep-fried fish were displayed in the window of Victory Fish Bar. I read ‘Victory Fish Bar’ as ‘Victoria Fish Bar’. The smell of sewage, the piles of waste, the dark, narrow streets, and the crossing of the Thames allowed me to imagine myself a Victorian.

In the twenty-first century I checked my step-o-metre. We had come 3000 since leaving the station. Steps, that is. That’s approximately 2.286 kilometres. Or 1.4204545454545454 recurring miles. We could have got the P12 bus, I realised and regretted later (I had already walked – upwards of – 15,000 steps earlier that day), but we didn’t know it then.

Destination Jupiter Woods, an art space in Bermondsey made from an old house and a garden, hovering between Affordable Housing and Demolition, by which I mean it was once a family home and one day it will be rubble, but for the moment it’s a place where artists work and exhibit.

Click now, https://jupiterwoods.com.

Artists are short on space.

If you think this is because line graphs of population are forever rising, you are wrong.

In the backyard of the Jupiter Woods house M and B have constructed the conditions of a potential ecosystem – not quite as low-key as primordial soup, but nor is it Masaai Mara. They have built planters from plastic milk bottles (semi-skimmed) and pinned them to the walls. Either M or B or both have coated the milk bottles with glow-in-the-dark paint, such that after a quick flash of torchlight, a faint green/blue haze rings out onto expectant faces. Oooooh, I say, forgetting myself for a moment. Aaaaah, I say, overtaken by the sensation of looking at light.

Glow-in-the-dark paint is not a necessary requirement of habitat-creation, but it helps.

Inside there are lines of germination trays, covered so as to keep the moisture in but the rain out: the water levels need to be Just Right. Each seed will be given its own little cell. It will live in the same encasement as the others, but separated by a thin wall. This is possibly to give each little seed the best chance in life, or possibly so their human carers can tell them apart, remember which is which, distinguish A from B. Each of these tiny seeds has a name and a story and a unique future that exists in the present in the sense that it is already mapped out. But for the time being, to the untrained eye, they look very much the same.

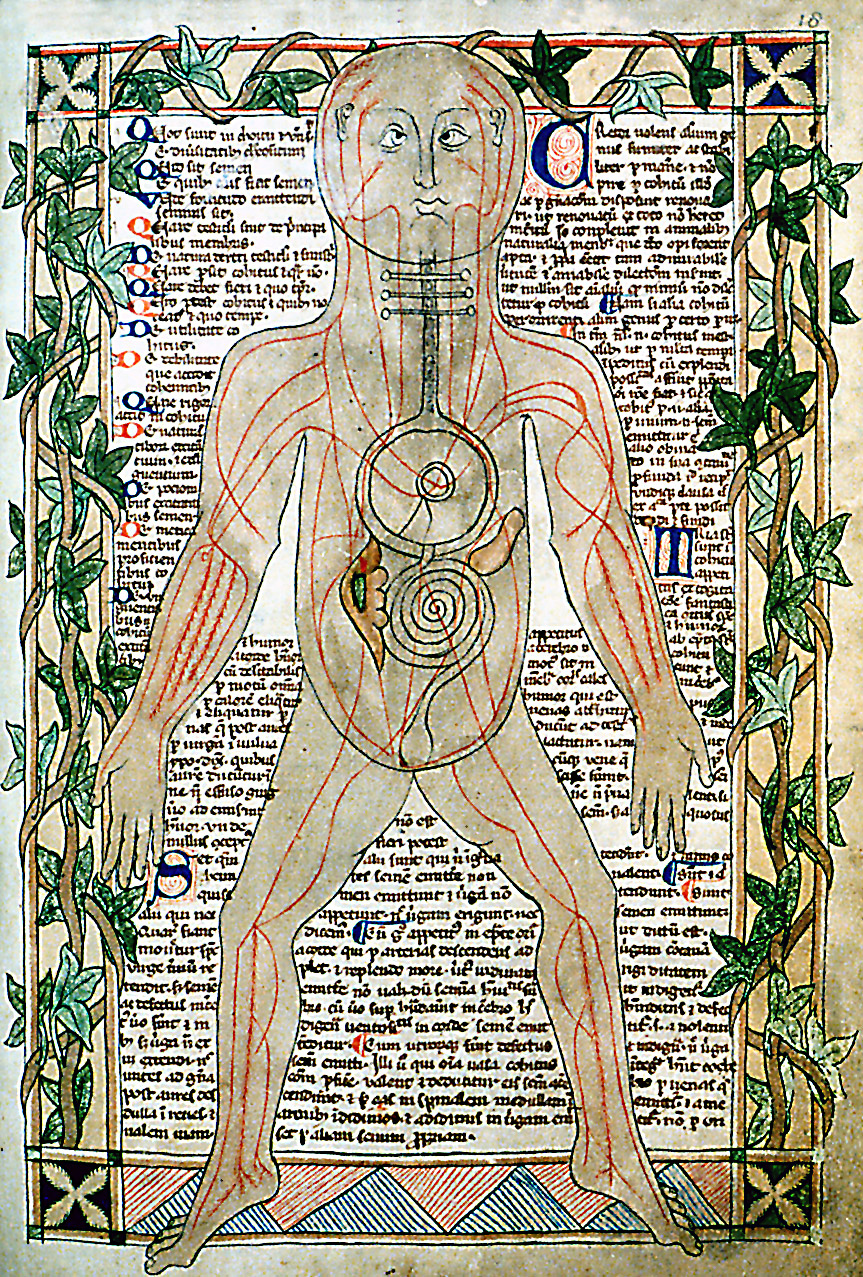

We are offered exclusive consultations. The plants that are offered are medicinal. We must each choose one, according to our symptoms and their properties, and the discussed prescription. The chosen herb will be planted, cared for, and harvested when the time comes. Then it will be ingested by its patient. That might be in the spring. Or it might be in seven years.

Chamomile tea is enjoyed for its taste.

If you have hay-fever or allergies to ragweed, you may find chamomile has the same effect.

The botanical name for St John’s Wort is Hypericum Perforatum.

Cat’s claw contains chemicals that might stimulate the immune system.

Traditional uses of bugleweed include the treatment of nosebleeds.

I read about plants and gardens in medieval documents. I read about the fields of Peckham, the marshes of Hackney, about trees planted on the banks of the foss around Newgate Prison. I read about the damp, grassy moor of Moorgate before it was a tube station and a Vodafone shop and a centre of world banking.

Plants are short on space too. But, sometimes, they manage to cut through concrete. In a way that is kind of satirical, don’t you think?

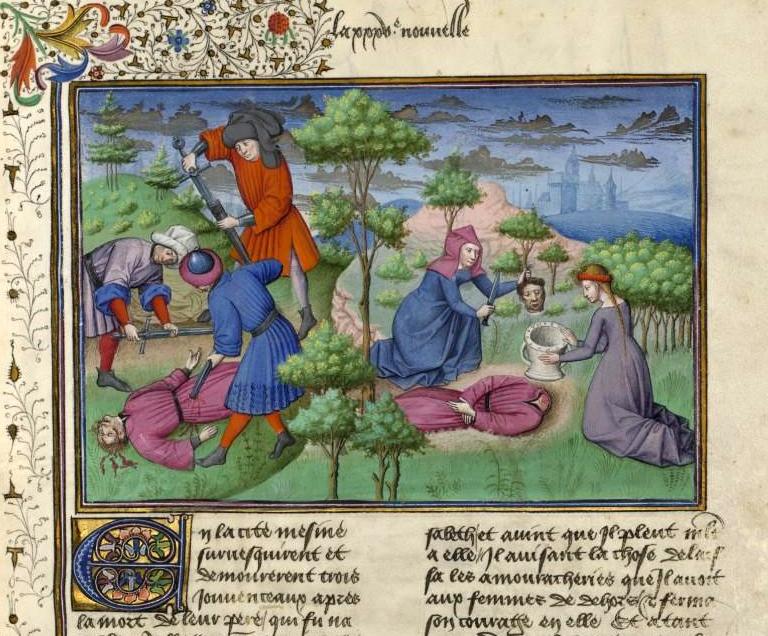

There is a document, dated 1412, describing an incident near the Tower of London. William Button (a clerk), John Leek (who worked with leather) and several other men of the City of London attacked and destroyed the earthen walls of a neighbour’s garden and pinned a notice to the gate. It was a warning: they threatened further action if their demands were not met. The neighbour was instructed to gather up and remove from the walled garden all herbs/plants and trees before the mob returned to destroy these too.

“Here hath ben this nyght a cumpanye of trewe men by comen assent of alle this worshipfull Citee to warne yow with a litel stroke or more harme come to gader up your erbys & trees or ellys it shal al be destried right as ye see for we wole have our grounde whos evyr be grucche it…”

“Here has been this night a company of true men by common assent of all this worshipful city to warn you with a little stroke or more harm come to gather up your herbs & trees or else it shall all be destroyed right as you see for we will have our ground whosoever begrudge it…”

It is unclear what type of herbs these were, and it is unclear what kind of garden this was. The plants may have been for eating or they may have been for looking at. Like the herbs in Jupiter Woods, they may have been medicinal. It is unclear why these men wanted the plants and trees to be removed, and why they wanted the walls to be torn down. Like so many documents in the historical record, the names and descriptions tantalise but ultimately elude.

Good historians don’t speculate.

Artists do.

If I had a go at speculating I would tell you a short story:

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the civic government of London enclosed a whole lot of land. Land that had been held ‘in common’; land that was designated ‘waste’; land that was inhabited by the poor, by beggars and sex workers; land that was considered dangerous for some (spurious) reason or other; land that was unproductive, by which I mean, of course, that it was not making anyone any money.

The land was enclosed. Walls were built around it. What had been public (in a sense) became private. What had been un-owned became owned.

It may be a familiar story. And I wonder if William Sutton and John Leek were caught up in it, if their complaint was against the building of walls around land that had previously been open, if they were ripping down earthworks and trampling plants because they objected to partitions in the landscape.