“The Habsburg Empire was indeed unique in the sense that the masses of the people which populated it lacked patriotism. In the Austrian Monarchy there were eleven nations but an Austrian nation as such never evolved… An Austrian nation never existed…”

– The Tragedy of Austria, Julius Braunthal, 1948, p.18.

Austria or Österreich (“East Empire” in German) was originally founded by the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne in the year 796, as a provincial defence outpost. Intended to protect the Holy Roman Empire against the threat of Turkish invasion. The Habsburg dynasty ruled Austria from 1282 until their Empire collapsed in 1918, following the First World War. The province of Austria consisted of eleven lands including German, Czech, Slovenian, Ruthenian, Italian, Serb, Croatian, Rumanian, Hungarian, Galician and Bukinovan populations, although Austria never really managed to unify this mass into a cohesive national identity. Leader Francis I, the First Emperor of Austria, would capitalise on this sentiment from 1815 onwards in a bid to maintain dominance over its existence.

“I keep down the Italians by means of the Hungarians and the Hungarians by the means of the Italians, their mutual apathy produces order and their mutual hatred produces general peace”.

Following the Austrian defeat in the war with Prussia in 1866, the Austrian Empire was divided up with Hungary as part of the 1867 “Ausgleich”, or “Compromise”, with Serbs, Slovaks, and Rumanians being forced to integrate and assimilate into Hungarian culture. This move further empowered pan-Slavic movements and in particular pan- German movements, the latter of whom were previously against Napoleon during the wars with France. This empowerment, alongside rising anti- semitism, would make the the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938, known as the Anschluss, an increasing reality.

One space that did offer sanctuary for crowds to come together during the nineteen century were the coffeehouses of Vienna. For the price of a cup of coffee, a patron could stay for several hours and be part of what Ray Oldenberg terms the “third space”, home away from home existing somewhere between public and private spheres. In his first book “The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere,” philosopher Jürgen Habermas presented the coffee houses of London as a space for a group of private individuals to come together as a public and create shared discourse. This bourgeois public sphere is described by Habermas as declining in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into a passive culture of mass consumption rather than public discourse. In Austria, however, there were strict rulings on the public expression of political opinions, which was prohibited until 1848, making discourse or more importantly, dissent, subject to strict policing. As a consequence, Vienna’s intellectual public sphere developed in a different way to London’s, with discursive cafe society and mass culture simultaneously coming together in a much shorter period of time. As politics had been forbidden as a subject of public discussion, conversations prior to this had mainly been of the aesthetic realm. The coffeehouses provided a literal and metaphorical escape from the threatening outside world. They were frequented by a largely Jewish population, and spaces such as Cafe Tirolerhof and Cafe Scheidl were early meeting places for homosexuals and lesbians.

In the early 1900s, outside the Cafe, Vienna was being modernised under the Christian Social mayor Karl Lueger. He significantly modernised conditions in the city, providing alpine drinking water and modern social housing, while at the same time aggravating a wave of anti-semitic sentiment. (Hitler lived in Vienna between 1907 and 1913, and it was said he was influenced by Lueger’s views). The Dreyfuss Affair (1894–1906) was still fresh in peoples’ minds and pan-German movements seized on this moment where questions of Jewish assimilation were being considered alongside emerging nationalist identification. Austria’s conservative Christian Social Party would flit between ‘socialism’ and, fascism, monarchical and republican sentiments, as each opportune moment arose – a man without qualities. A deep cynicism pervaded the Austrian psyche.

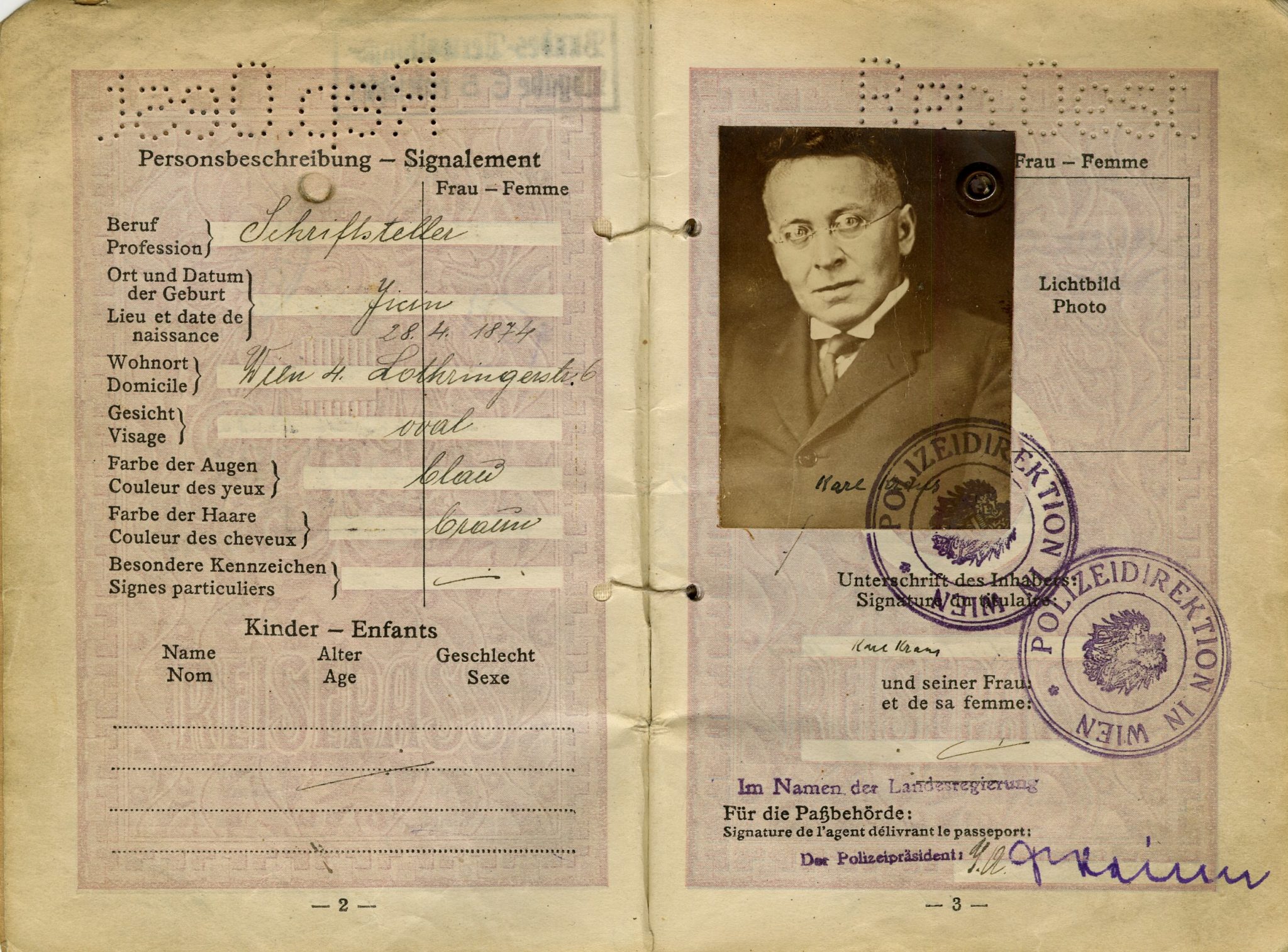

Against this backdrop, groups of artists and thinkers reacted to this by attacking the rotten edifice of the social fabric, which longed for Biedermeier decoration. A modernist impulse looked towards the disintegration of these forms in architecture (Adolf Loos), language (Karl Kraus), music (Arnold Schoenberg), psychology (Sigmund Freud) and philosophy (Ludwig Wittgenstein). The writer Karl Kraus famously labelled Vienna as a “research laboratory for world destruction”, and went on to produce the biting, satirical magazine “Die Fackel” (The Torch) aimed at changing the status quo.

Kraus was born in 1874 in Jičín, Bohemia (now western Czech Republic), into a wealthy family who manufactured paper. After a spell attempting to become an actor, he began writing for the Neue Freie Presse, the leading paper in Vienna. Due to his impressive writing, Kraus was offered the position of chief satirical writer for the paper in 1898. He responded by quitting, and founded his own magazine “Die Fackel” the following year, which would go on to attack the activities of the Viennese press, including his former employers.

Prior to Die Fackel, Kraus had published a satirical pamphlet in 1898 titled “Demolished Literature”, (Die Demolirte Litteratur) expressing his growing alienation from the Impressionist group of contemporary writers known as “Jung Wien (Young Vienna)”, of which he had been considered a part. The text was a deconstruction of the literary circles and social conventions that took place inside the Cafe Griensteidl. It opened with the sentence “Wien wird jetzt zur Großstadt demolirt” (“ Vienna is being demolished into a great city”) and was published at the time of the demolition of the actual space.

Die Fackel ran until Kraus’ death in 1936. Initially taking on contributors, he ran and wrote the magazine by himself from 1911. Attacking the emptiness and corruption of Austrian life, Kraus defined Die Fackel not by “was wir bringen” (“what we bring”) but rather “was wir umbringen” (“what we destroy”). He wanted to shatter the quaint picturesque image of the “Viennese” that was being projected to the outside world. Kraus’ targets would often be the Left, mainly because he felt the idiocy of the Right to be self-evident. His satire was usually culture instead of politics. Before 1914 he had supported the conservative forces, because of his hatred of those dehumanising forces of technological forces and mass democracy which he associated with the press.

At the outset of the First World War, many intellectuals were in favour of the war, including composers Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg, who thought that their violent fantasies for destruction would be fulfilled on the frontlines. Freud said he finally felt he was Austrian (“ All my libido is given to Austria- Hungary”). Due to bad health, Kraus never had to serve military service, instead getting reports from the trenches from friends such as fellow writer and publisher Ludwig von Ficker. Many soldiers wrote to Kraus expressing support for him, and telling how they would read Die Fackel while between shifts in the trenches. Kraus was fiercely outspoken against it, a position which he was virtually alone in during the first years. Mahler would famously express similar, contemporaneous alienation, lamenting himself as “thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed”.

From 1916, Kraus went on to write his epic satire, “Die Letzte Tage der Menschheit” (The Last Days of Mankind), publishing excerpts in Die Fackel. An anti-war opera in five parts and lasting ten days, it was to be performed on Mars (because people on Earth could not bear the reality presented to them). Due to the war censor, it was finally finished in 1922. Shockingly, the most horrifying parts were mere quotations of actual existing events, such as a frontispiece photo of Austrian socialist Cesare Battisti who had been executed in Italy in 1916 by Austrian authorities, causing further unrest to Italian subjects of the Empire. The work was a large collage of actual found footage, news reports, historical incidents, elements of symbolism culminating in the Last Night with scenes of slaughter, and human suffering giving way to the chanting of a choir of hyenas (war profiteers) whose leader (the head of the Neue Freie Presse) declares “ I am the Antichrist”. Mankind destroys itself in a hail of fire and the play ends with the voice of God saying “Ich habe es nicht gewollt” (“I did not want it”), words attributed to the German Kaiser Wilhelm II at the beginning of the First World War”. Language revenges itself on those who pervert it or use it idly.

Many of these intellectuals would be on the frontlines, and confronted with the reality of war, would realise how much of a mistake the war was. Wittgenstein would finish his Tractatus work and Berg, having suffered a physical breakdown, would write notes that became his opera Wozzeck. Playwright Bertolt Brecht praised Kraus’ opera, stating that its mixture of naturalism and symbolism had influenced his own plays Mother Courage and Her Children (1939) and Fear and Misery in the Third Reich (1938).

Kraus shows that, whilst far from being a perfect person ( if that even exists) in spite of impending doom, satire or gallows humour can be a vital antidote, essential maybe, in desperate times of need.