Some worlds are born soft as a kiss. Soft

And spilling from one mouth to another, or hurling

Like atom split, or slick blood

And tears while the cord is cut.

Here is the story of how the world I’m living in came to be.

This one was conjured and it came searing.

It was a Monday, almost ten years ago, that the birth began. The moon waned in Capricorn as the Medicine Woman was sleeping. Wet tyres hushed past on the North London road below as she soared. Her dreams usually took her back to red soil. The morning sun pressed against her skin and oiled hair, parted down the middle, as she cast eyes over the garden. Dew had become a fragrant vapour that hung fertile in the air. Her Bantu friends would say that you could throw carpet dust on this soil and something plump and juicy would grow from it.

She laughed to herself at the sight of the fallen jungli-pears covering half the ground. It was only when she moved halfway across the globe, and ate the jungli-pears brought over from still further across, that she realised ‘avocados’, although expensive, were actually quite delicious. One fell with a gentle thud by her foot. Crouching, she turned it over in her hands and decided it would be pickled later that afternoon. The breeze combed through the papaya tree’s leaves and the banana flower prepared to drop its daily petal.

Taking care of her arthritic knees, she slowly knelt by the sprouting mung and began her day’s work. The dull ache of her joints came with her to the garden but found some release in dreamtime labour with dirt. Easing pods from stem, her hands became quicker as they remembered the choreography and she tuned into the surrounding birdchatter. “Good morning, pitru.” She wondered how, in the flocking journeys between realms, they greeted each other before exchanging messages from the Has Been and Yet-To-Be. In the early years in London, when this dreamgarden was more of a dreamforest, the mocking, mournful birds would guide her to the medicine.

When her son my uncle contracted jaundice and Great Ormond Street Hospital started talking about needles and steroids, she went straight back home with him bundled in her arms. Running through the forest in a fever dream that night, searching searching sweating and searching, an old heron with one good eye flew low and steadied himself on top of a patch of sugarcane. She withdrew her machete and began to hack at the stems. Crying crying and cutting until heron was satisfied and flew again. The next morning, at her friend from the factory’s husband’s fruit and veg shop, she asked for seven stalks of sugarcane. Stripping the skin, she gave them to her yellow son to suck on, and told him to perch his yellow feet on the growing pile of sugarless husks. Over the next hour, she saw the frayed cane under his feet become the same shade as her son, as they drew the jaundice from his little body. Heron’s sugarcane, mung and milk eventually frightened the virus off with their insistence on sweet, slow sustenance. The mung pods filled the wide basket now, and she swung it across her hip to go and sit in mango shade.

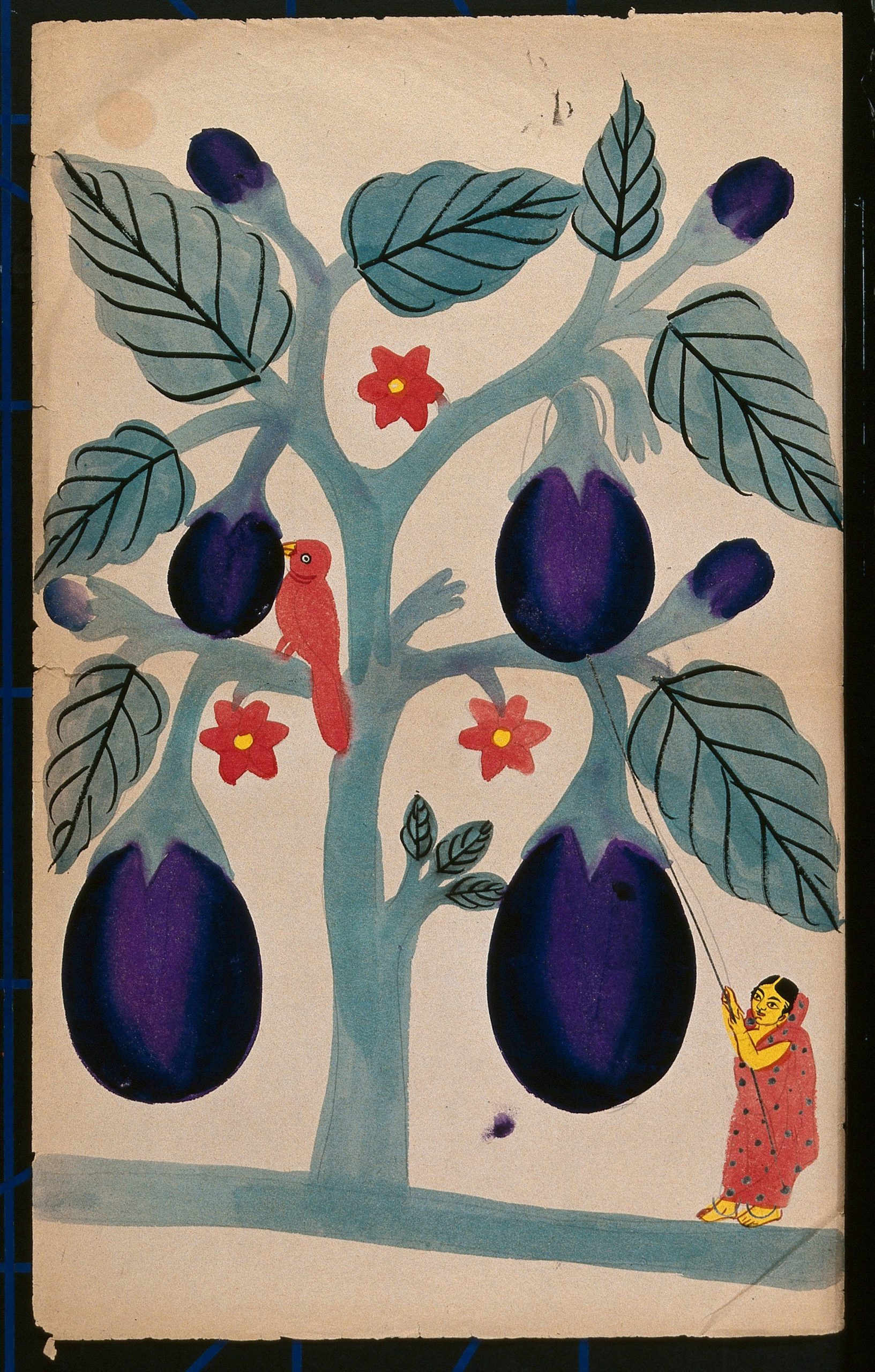

Beginning to sift the pods, her attention was pulled to whistling somewhere over her shoulder. She turned and saw three red bulbuls chasing one another, and circling above a strangely clear patch of land. Dusting off her apron she made her way over, sensing mint near the roses in passing, maybe good with tomorrow’s brinjal. The soil under the calling birds was warm and wet, and as she sunk her fingers, she felt a beating. Absently looking for a dismembered root or seed, her searching fingers went deeper as the beating grew loud and fast. The bulbuls were becoming frenzied as the midday sun scorched and echoed the soil’s pulse.

Straining their trilled throats, more like screeching now, she was elbow deep. Feeling desperately for something to hold onto in the pounding soil. The sun raged on her scalp, down her parting. Tears streaming and breath growing ragged, she dug her heels into the ground, praying for it to open under her. The sun doubled down its efforts to split her in two. Her hands in dreamsoil now reaching for why and why and why. She pulled one hand out to try and cast a forgiving shadow but the sun was intent, and the left side of her head seared bright hot. Eyes clasped shut, her fingers scratched at something underground and finally held on. Silent screaming, the gardenforest twisted. Fruits adrift and a mess. The erratic beating was now in the middle of her chest. Her right hand and heel still deep in soil, she was pulled spinning through the sky.

Awake. She was in her bed and it was dark and she was sweating and panting, everything else rippling around her as she tried to shout. Black. Light switched on. Black. Green uniform. Blue flashing. Black.

She tried to loosen scrambled thoughts. She knew she was leaving her room and home. Wondering if the bulbuls had taken her to some penumbral half-space. Black and blurry, maybe they’d forgotten her on the wayside between the there and thereafter. Beating beating.

Only two family members at a time

Please

…talk slowly they said.

Be Descriptive to evoke the senses.

…help parts of the brain awaken again

…window of recovery.

Naniji, when you’re Back Home i’ll put Oil in Your Hair

And we’ll sit in the Garden

And Feed the Blackbirds Warm Milk and Old Rotli

Spring is coming and the Wind will be Fresh.

Enunciating to be Very Sure

the words stayed intact from (lump in) throat to ears,

Which stay tall and open day and night.

Bright cold white. In another bed now, Medicine Woman is sleeping. A dreamless morphine-haze sleep. Her body heavy, she breathes in pentatonic scales.

…Naniji listen to this song it’s your favourite song

Itni toh araj suno, hai path mein andhiyaare, de do vardaan mein ujiyaare[1]

She wails, a cry from somewhere different

She doesn’t like it says the ICU doctor

She loves it I say

Frustrated that with all his experience he doesn’t seem to know

That salt and lament make potent tonic.

Medicine Woman can hear everything, and especially better when they move their mouth a lot while sounding out the words with unbroken eye contact. She wants to adjust herself but feels a weight keeping her down. A few days later, she knows the weight is on the right side of her body. Her arm and leg still, in a deeper sleep than the rest of her. The fluorescent lights feel sticky on her face and she remembers the angry sun and the smell of rain and hands. Yes, that was it, she was in the Garden. And there was something there and she needed it and. Sleep. She felt her heavy hand, now cloudlike, sensing the soil and something there, and it was holding on.

Tears gathering between her puffy eyelids, she storms through that blurry Middle, where the birds chatter as she looks for the sun, to look it in the eye and ask why why why. Words like clot and block and blood came whispering through the sky on those long dark walks, and then screeching words like cell death, paralysis, brain damage, and hissing ones like unlikely and luckily and unfortunately.

The birth came searing

Through the top of your head,

Ushered by the bulbuls,

It was invoked.

As time passes, the why becomes less loud

And the how many, at what time, where does it hurt, and can I hug you become more pressing.

Now home,

Plums filling with juice in the front garden

While local foxes share secret bin treasure,

we are each touched

By Change. Each touched and each changed

Like I said, sometimes it comes soft as a kiss

Or fragile incremental as ant feet. But it comes

And it reconfigures our circuitry such that

We become again. And again.

We deeplisten, and slowspeak

And we keep trying until we meet each other.

Since the sun bore a hole through her hair that night and the sky tried to swallow her as she held on holds on to that something in phantom wet soil, we are different again. Medicine Woman, holding our hands, led us through this threshold. The House and its door looked just the same, same stained glass and peeling WWF and NSPCC stickers. Stepping clumsily, with sleepless tears, we crossed. With a dreambody split in two by the sun, one half still holding on in a garden of eternal morning, copper skin meeting melting with copper soil, we honour this new world with the parts of the old one we remembered to dry or jar. Sung to by the curious or otherwise indifferent phantom birds.

When Medicine Woman sleeps and soars, she finds herself in dark halfspaces and unruly dreamgardens again. Sometimes her wheelchair comes with her, sometimes not, other times her heavy side stays still and heavy, other times not. For the first year, there were no dreams, or they were the kind that you forget before you wake up. Then shapes and disembodied sounds appeared as apparitions. She cursed her daily meds that kept her foggy but alive. Without being able to cook, among other things, waking hours felt drawn out and draining. Her inside voices were louder than before, speaking on top of each other. Passing daydreams and urgent questions slipping past each other, hard to decipher, harder to pin down and almost impossible to push out through her mouth. Her family grew their ears to listen better.

The rhythms of the day, our bodies and voices have changed. Our capacities, tendencies and affordances shifted. Still entirely whole, touching and co-present, and now entirely more brown in the way that José Esteban Muñoz’s ghost tells it. “Brownness is a being with, being alongside.”[2] The House and its People: carers, commons, living infrastructure. Laying bare the very fact that we are each others’ spawn and crutch. Intergenerational lives intergenerating life as our main occupation, no luxuries of self-absorption. The House is the locus of care, and the Medicine Woman, was and is the locus of the locus of care. And only locus insofar as the ways of this world were spun on her axes. Barefaced grief is one axis. I don’t know where the other axes come from or go. We orbit in unknowability. “To think about brownness is to accept that it arrives to us, we attune to it only partially. Pieces resist knowing and being knowable,” says Muñoz’s ghost.[3]

So, language proliferates on this side of the portal. Three types of English, two types of Gujarati, clipped Swahili and evening Sanskrit. Medicine Woman teaches us new ways of listening and speaking. We have a new alphabet, and she only really has use for vowels. Ancient Greek-Latin-pharmabranding has us stretch our mouths in shapes like lansoprazole, warfarin, furosemide and clopidogrel. Sentences are formed by one or two hands and two or more mouths. Medicine Woman begins by sounding out or hand signing, and we each fill the in-between space until we reach common ground. Those sometimes quick always fraught moments of co-remembering and co-speaking steep us in shared undivided attention.

Her hands look like cousins. One of them is soft and stiff at the same time, curled and resting on her resting leg. The other has a knuckle like a hill with robust river veins and is always moving. The right hand, that knew like instinct how big a pinch of cumin should be, and how to carry suitcase and daughters across continents, now sits stubborn and content in not doing. Almost all doing is done by the left, which writes wobbly letters and speaks with all four fingers and thumb. Not in a sign language that was ever taught or learnt, but one that we all made up on the spot.

In age order, baby finger for my unyellow uncle, weary-resolute ring finger for my mum, nevernot slightlyfunny middle finger for my middle aunt, first finger for first daughter and a tired thumbs up for my grandad who only started loving her fiercely post-stroke. The digits then cross to show relations, bend to show size and fan out to ask who or what or why. Achey articulations: hasta prana, the life of the hand. Mudras sealing meaning, fixed and fluid enough to be claimed back and forward by daily change. Gesture and co-spoken sentences limited only by the overlap of our shared memory and immediate awareness.

Years after that last night she slept upstairs, Medicine Woman returns to her medicine garden where nothing is white, hard or effervescent. It’s overgrown, the trees are swollen with bird nests, and papaya (co-spoken as pa-pai) has flourished. It soothes heart and gut, a warming, tonifying fruit. Eaten daily. Some nights she works the weeds and harvest, other nights she simply lays the length of her body on the red soil and listens to the gurgle of the earth decomposing this and birthing that.

We live at the pace of our limbs and organs. The House renders us “anomalies in chrononormativity”, as Yasmin Gunaratnam might say.[4] Swinging around the tunnel of standardised time that assigns our value in cold, griefless ways. You, ushered by the bulbuls, cut open a new world to look after us in. For the longest time, living and loving here felt like I was bursting. My inner clock felt like a broken egg timer, nervous system unable to keep up with the shifting time zones of each world I occupied. They all pestled against each other, one demanded more while another pleaded less.

But recently, all the worlds have slown,

Somehow eventually beating

At the pace of This House and its organs.

Across the tangled axes of ongoing care

And grief,

And free-sung joy,

Between the Has Been and Yet-To-Be.

And I put my ear against yours and say please take me there,

I’m listening.

References for things that were explicitly or implicitly involved:

[1] Translation from Hindi: “Please hear this plea, there is darkness in this path, provide us with Blessed Light”

‘O Paalanhaare’. 2001. Lagaan (soundtrack). Lata Mangeshkar, Sadhana Sargam, Udit Narayan & Chorus. A. R. Rahman.

[2] Muñoz, José Esteban. 2018. Preface: Fragment from The Sense of Brown Manuscript, in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 395-397. https://read.dukeupress.edu/glq/article/24/4/395/135967/PrefaceFragment-from-the-Sense-of-Brown-Manuscript

[3] Ibid.

[4] “As economically unproductive, dependent and unruly bodies, debilitated and dying migrants are anomalies within the ‘chrononormativity’ of late capitalist economies.” p14

Gunaratnam, Yasmin. 2019. ‘Those that resemble flies from a distance’: Performing Research. MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture, Summer(4) http://research.gold.ac.uk/26346/

✻

“The spirit is a floral cotton jungle breathing in pentatonic scales.”

Anjali, Manisha. 2019. ‘the thread is made of flesh’ https://manishaanjali.com/the-thread-is-made-of-flesh

“I say mujer magica, empty yourself. Shock yourself into new ways of perceiving the world…” p.172

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1983. ‘Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to 3rd World Women Writers’. In: Moraga, C, Anzaldúa, G (eds) This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 3rd ed. New York: Kitchen Table Press, pp. 165-174.

Barba, Eugenio and Savarese, Nicola. 2011. A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer. Taylor & Francis. pp. 156-157.

“Conjure feminism is an embodied theory that recognizes the importance of spirit work in the development of Black feminist intellectual traditions.”

Brooks, Kinitra. ‘Myrtle’s Medicine’. Emergence Magazine. https://emergencemagazine.org/story/myrtles-medicine/

The Hologram: Social Medicine for a Cooperative Species. http://thehologram.xyz/

“Disability Justice is a vision and practice of a yet-to-be, a map that we create with our ancestors and our great-grandchildren onward, in the width and depth of our multiplicities and histories, a movement towards a world in which every body and mind is known as beautiful.” p.22

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. 2018. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

“How can I relate respectfully to the other participants involved in this research so that together we can form a stronger relationship with the idea that we will share? … Am I being responsible in fulfilling my role and obligations to the other participants, to the topic and to all of my relations? What am I contributing or giving back to the relationship? Is the sharing, growth and learning that is taking place reciprocal?” p.77

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research as Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

✻

“Sickness” as we speak of it today is a capitalist construct, as is its perceived binary opposite, “wellness.” The “well” person is the person well enough to go to work. The “sick” person is the one who can’t. What is so destructive about conceiving of wellness as the default, as the standard mode of existence, is that it invents illness as temporary. When being sick is an abhorrence to the norm, it allows us to conceive of care and support in the same way.

Care, in this configuration, is only required sometimes. When sickness is temporary, care is not normal.

Here’s an exercise: go to the mirror, look yourself in the face, and say out loud: “To take care of you is not normal. I can only do it temporarily.” Saying this to yourself will merely be an echo of what the world repeats al the time.”

Hedva, Johanna. ‘Sick Woman Theory’. Mask Magazine. 19 Jan 2016. http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory