The resurrection of the past tends to take on quasi-hallucinatory forms [1]

Works of sci fi and speculative fiction allow us to remember our own future. The search for what is most significant in the recent past is glaringly apparent in works of art and literature from all eras that throw conjecture on to times ahead. It is no coincidence that futuristic visions from the 1960s and ‘70s were saturated with a space-age aesthetic just when the exploration of space had been a huge priority for many countries. Or that HG Wells’s works – written at a time when advancement in biomedical science had been rapidly advancing – are filled with tales of strange vivisections and curious medical developments.

The story of The Hunger Games repeats history in its vision of the future both overtly and obliquely: the idea of ‘as before, so it must be again’ is littered throughout. The story draws on the currently impending climate crisis as a way to effectively raze North America, which resurfaces as the state of Panem. This crisis is set in the story’s recent past, allowing currents of power and oppression in the subsequently-formed infrastructure to come to the fore.

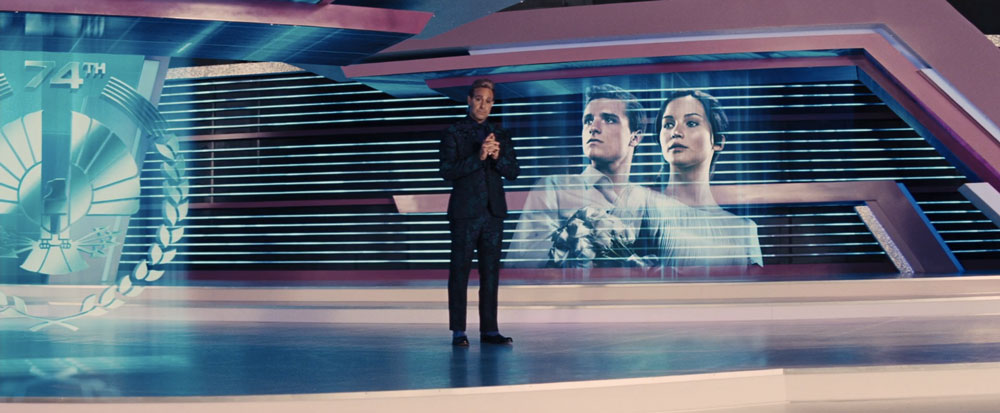

We learn that the nation of Panem consists of 12 half-starved districts in which the people work laboriously for a subsistence wage. The labour of these districts supports a wealthy, technologically advanced ‘Capitol’, and the elite minority of citizens living within. From this Capitol an autocratic government tightly controls its citizens. As punishment for an attempted revolution 75 years ago, two adolescents per district are selected at random each year in a ‘reaping’ to compete in the annual ‘Hunger Games’. Like untrained Roman gladiators in a glitzy reality-TV contest, they are forced to fight to the death in a high-tech arena, the broadcast of which is compulsory viewing in the districts. This systematically enforced, grisly sacrifice of the districts’ children is an effective form of oppression, while also providing entertainment for the elite citizens of the Capitol.

Significantly, The Hunger Games visualises its future setting by drawing heavily on classical archetypes. Take for example the arena’s ‘Cornucopia’, which is named after and resembles the shell-shaped provider of life and bounty of classical mythology. The selected children are initially drawn to fight for supplies in the mouth of the Cornucopia, where many of them die. Indeed the very idea of ‘reaping’ a selection of the people’s children for sacrifice comes from Theseus and the Minotaur, in which the oppressive state of Crete did just that. The name ‘Panem’ comes from the Latin phrase ‘Panem et Circenses’: a metonymic (originating from the Roman poet Juvenal) for the superficial appeasement of citizens through entertainment or diversion. The people (of the Capitol) are pampered, but by forgoing their political responsibility they have given up all power.

Even the protagonist’s character develops along the same arc as Spartacus: from oppressed to prisoner to revolutionary. Classical paradigms are well placed to shape visions of the future as they are good, unobtrusive signifiers. They are largely embedded in European cultural awareness, and layered in meaning: most people can vaguely register the symbolism of a cornucopia, for instance, without it holding an established place in everyday life. Its being from the distant past makes it an uncommon object, which serves to differentiate the chronological context of the story from the present. The cornucopia is emblematic, decipherable, but estranged from the commonplace. It both signifies a gulf in time and makes the future vision readable.

Through the application of ancient symbols alongside advanced technologies, extreme inequality and emerging norms like reality TV, The Hunger Games achieves an almost Borgesian [2] manipulation of time: a possible future is ‘remembered’ in which past, present, and future coexist on different levels.

In many works that project speculation onto the future, this device occurs routinely because it mirrors a fundamental function of the brain. It comes from the same neurological process that allows us to reasonably predict the next hour, the next day, the next year in our day-to-day lives. To comprehend it fully requires an understanding of the neurological processes that underlie mnemonic function.

It may be helpful to begin by noting that the act of remembering happens in the present tense, and is a process of construction rather than retrieval. In the moment of recall, one pulls together mnemonic fragments to create a narrative of the past that best fits the present.

This seems contrary to all that we know. When dealing with the topic of memory our vocabulary is littered with words associated with permanence and unchangeability: ‘imprint’, ‘burn’, ‘sear’, and ‘brand’ are commonly-used terms when discussing the forging of strong recollections. This is extremely reflective of how memory is commonly perceived to work. We tend to rely on memory as though it were a cache of static, largely-infallible heirlooms in the recesses of the mind – to be retrieved, whole, at a later date.

Anyone who has misremembered or struggled to recall crucial details knows that the act of recall is in fact ambiguous and deeply unreliable. Individual recollections are inevitably coloured by the views and feelings of the current rememberer, overriding those of the protagonist of the memory (the previous self). It is impossible to wade back in time so entirely as to forget the things we’ve learnt since, and refrain from projecting them onto the recollection itself. To do so would mean negating the time that had passed: unlearning the life lived since and reverting to an earlier incarnation of ourselves. To remember is not necessarily to re-live an experience accurately: it is to view fragments through the distorting haze of time, and from them construct a coherent narrative that serves us best in the present moment.

This act of generalisation seems deeply ambiguous, but it’s what makes memory meaningful. It crucially allows us to place ourselves in chronological context by identifying pattern and repetition – without which we are lost.

By spotting recurrent fragments we can begin to recognise patterns, and so create predictions of possibilities. Works of speculative fiction expand this aspect of mnemonic function by pulling together fragments of the reader’s present, and developing them along a sharp trajectory to their most extreme conclusion. By defamiliarising their setting through injections of symbolism from the past, they can be presented as though viewed across a gulf of time, giving the illusion of futurity.

There are two ways, then, that we can perceive repetition within our own memories: through recurrence (events happening more than once in some form) and reappearance (people and figures cropping up repeatedly, whether symbolically or actually). The Hunger Games deals heavily in reappearance, as the entire story is haunted by figures from the distant, collectively remembered past through nomenclature.

In particular, citizens of the Capitol tend to have classical Roman names, inviting direct connotations of violence, privilege, and barbarism, as well as cementing their position as oppressors. Individual names conjure up specific ghosts from our past, providing a shortcut to cementing characters’ ‘place’ in the story: Coriolanus Snow, Capitol president (Shakespeare’s Coriolanus ‘supported the power of aristocrats over the common people’); Caeser Flickerman (named after Julius) is the glitzy, flamboyant presenter of the Games and the ‘face’ of the Capitol; Seneca Crane, orchestrator of the Games (after the Roman philosopher [3] who was forced to commit suicide when accused of conspiracy, mirroring Crane’s execution); Cinna, Capitol-citizen and secret revolutionary (namesake of the poet in Shakespeare’s Julius Caeser, who was mistaken for a politician who helped kill Caesar and was subsequently killed by a mob. This foreshadows the fate of this Cinna at the hands of the Capitol).[4]

These names act not just as ghostly signifiers, but also serve to once again differentiate the time-frame of these occurrences from the present: these are not the kinds of names we give to our children.

The story also deals heavily in event-based recurrence: the evolution of insidious vouyerisms like reality TV into overtly barbaric models of entertainment constitutes another injection of history into the present. Like other works in which the state subjects its citizens to novel forms of oppression – think of the genteel sexual slavery of women in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale – this barbarism is coupled with a level of ritual which is now uncommon, and would seem to belong to the past.

The scenes of the Capitol could be 1930s Nuremberg – with huge eagle banners and glistening, neo-classically symmetrical buildings – the perfect example of historical patterns shaping a narrative of things to come. The neo-classical architecture of 1930s fascism itself refers to the ancient classical structures made to show the dominance and sophistication of its creators – a memory of a memory. Fragments of past imagery become archetypes, resurfacing again and again and repeating into the future.

***

Jay Drinkall is a writer living in London. She co-runs the project Three Letter Words.

[1] RICOEUR, Paul. 2012. “Memories and Images” (2004). Translated by Kathleen Blamey and Davis Pellauer. In Ian FARR (ed.). Memory: Documents of Contemporary Art. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp.66-70

[2] BORGES, Jorge Luis. 1964. “A New Refutation of Time” (1946). Labyrinths. Translated by James E. Irby, pp.252-269.

[3] Who said ‘It is one thing… to remember, another to know. To remember is to safeguard something entrusted to your memory, whereas to know, by contrast, is actually to make each item your own’

Seneca. 2008. A.S. BYATT and Harriet Harvey Wood (ed.). Memory: An Anthology. Great Britain: Chatto & Windus, p.160

[4] KRULE, Miriam. 2013. “The Hunger Names”. Slate [online]. Available at: https://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2013/11/21/hunger_games_catching_fire_names_exp