Shu Lea Cheang (TW/USA/FRANCE) is an artist, filmmaker and networker, constructing installation and multi-player performance in participatory impromptu mode. She drafts sci-fi narratives in her film scenarios and artwork imagination, building social interface with transgressive plots and open networks that permit public participation. Engaged in media activism and electronic art for two decades (the 80s and 90s) in New York city, Cheang concluded her NYC period with the first Guggenheim museum web art commission/collection BRANDON (1998-1999). She made two feature films, FRESH KILL (premiered at Berlin Film festival, 1994) and I.K.U. (premiered at Sundance film festival, 2000). From homesteading cyberspace in the 90s to her current retreat to post-crash BioNet zone, Cheang takes on viral love bio hacks in her current cycle of works. She is currently touring a collective ‘biogame’ UKI-enter the BioNet, finishing her cypherpunk feature FLUIDØ in Berlin and developing UKI, cinema interrupted with mobile media applications.

As part of Dream Babes and in the run up to Speculative Sex: I.K.U. and Neurosex Pornoia, artist Victoria Sin spoke with Shu Lea about science fiction as a medium to represent radical sexualities, and proposals for queer bodies occupied by technology.

Sin Wai Kin: You said to me that science and speculative fiction is your practice. Do you look at it as a medium in itself? What do science fiction narratives facilitate for you?

Shu Lea Cheang: I adopt science speculative fiction as a genre of practice. The medium as a tool, device, strategy, network, software, hardware, interface can vary in delivering a fictional narrative.

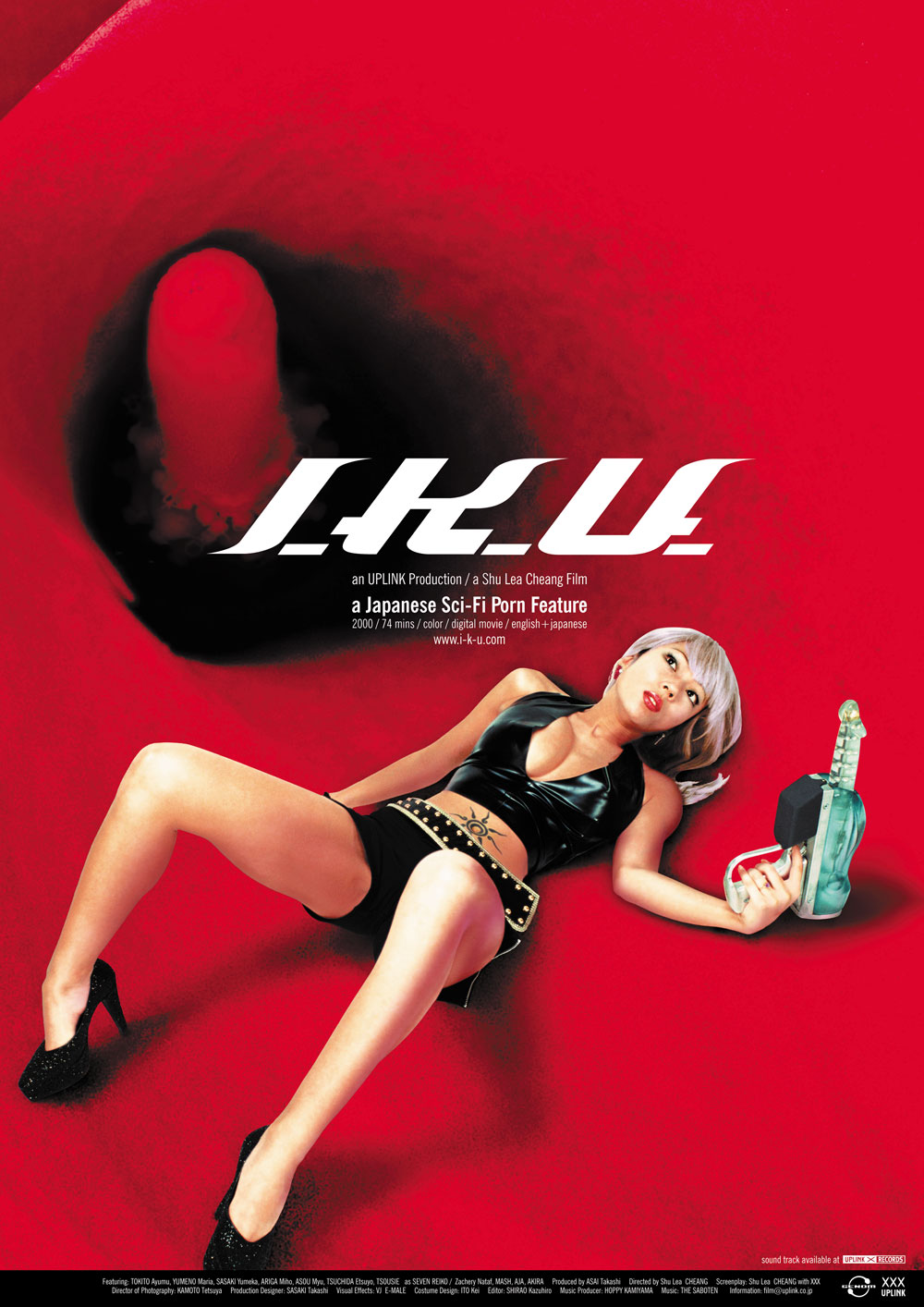

Your second feature film, I.K.U., premiered at Sundance in 2000 and was the first pornographic film to be shown there. I’ve read that at the premier half the audience walked out [1]. What difficulties did you encounter in the production and reception of the film?

I.K.U. was produced by Uplink Co. in Tokyo. The producer Asai Takashi invited me to make a porn film to challenge the Japanese censorship which specifically deems exposure of sexual organs illegal. I set out to make a science fiction porn, taking off from where Blade Runner ends with Dekkard and Rachael, the runner and the replicant, getting into the elevator and further pursue their unconsumed sexual desire. In the theatrical release in Japan, we have to cover more than 100 spots of exposed private parts by blacking them out on 35mm print. Over the years, somehow, I.K.U. became a cyberpunk cult classic, gets pirated in China and downloaded on Pirate Bay, a sign of its success, I guess.

I.K.U is groundbreaking in many ways. As a pornographic feature length film it depicts trans and cis gendered and raced bodies without fetishising them. How do you approach the casting and treatment of bodies in the making of a pornographic film or work?

The cast for I.K.U. in part are from Japan’s AV (Adult Video) industry where actors/actresses are managed and committed to various degree of sexual engagement in adult movies. The key part of the casting came from queer performance scenes in Japan. Connected to Dumb Type and its initial founding director Teiji Furuhashi, I got to meet a vibrant sexuality performance/show biz going on in Japan during my residency in Tokyo in the 90s. Gender were being tossed and played upon, queens and kings courted, sexuality performed loud. Many of these performers later were cast in I.K.U., i.e. Bubu and Akira as the couple in the elevator, Aja as Tokyo Rose inside the red web, Akechi Denki, the rope master. A special appearance is Zachery Nataf who played the main role Dizzy the runner. I met Zachery while doing research for Brandon web project in Amsterdam where he was getting sexual reassignment in the late 90s. At the time, I was quite engaged with the trans communities in San Francisco and Amsterdam. Zachery as runner debunks the myth of macho black sexuality. I also much appreciated Ayumu Tokito as Reiko who strode on open sexuality.

A lot of your narratives deal with the management of gender and sexuality in the future: corporations capitalising on aggregated sexual data, cybernetic beings who can change gender/form based on their partners desires. To what extent do you see technology permeating our lived reality of sex and gender?

Cyborg Manifesto (Donna Haraway), Cyberfeminist Manifesto (VNS Matrix) and Judith Butler’s writings on gender performativity published in the early 90s guided much of my work. In I.K.U. I designate the replicants with harddrive bodies for downloadable orgasm data collection. In the new movie FLUIDØ , mutated HIV virus re-codes body fluid as new sexual-sation drugs. The farming industry patents genetically modified seeds; the biotechnology industry goes on exploiting organisms, cells, genes, the living system; the DIY biohackers promotes open estrogen, bring back Betsey, Anarcha, and Lucy for gynecologists’ visits, the body apparatus wired and unwired, I cannot see any sex and gender without humanly possible intervention.

Following on from I.K.U. you created several sequels called UKI which took the forms of a 70 minute performance, and an interactive gaming scenario. How do you feel the various forms these sequels took changed or contributed to the narrative of the I.K.U. fiction?

Set your electric sheep free range.

It is 2060, what do you do with expired humanoids?

UKI is conceived as a sequel to my scifi cyberpunk film I.K.U. which tells the story of IKU (orgasm in Japanese) coders, dispatched by the internet porn enterprise GENOM Corp., and made into sex machines to collect human orgasm data. These programmed humanoids’ accumulated hard drive data are ultimately downloaded by IKU runners (á la Blade Runner) and made into color-coded orgasm chips for mobile phone plug in and consumption. In post-netcrash UKI, the data deprived IKU coders are dumped as pieces of e-trash amidst the discarded electronic parts and bits while GENOM Corp. takes human body hostage to initiate BioNet, a network made up of micro-computing red blood cells (erythrocytes). Inhabiting on the electronic trash-scape with the last remaining coders, hackers, and netters who work to patch self-sustainable networks, IKU coders unpack their body parts, rewrite the codes to reboot themselves. Trading sex for codes, code sexes code, the defunct IKU coders infected with body/software virus emerge amidst noise blast to declare themselves UKI the virus. Meanwhile, GENOM Corp.’s BioNet aims to re-program human orgasm into “self-sustained pleasure”, a profitable bio-scheme conspired without any precaution for damaging the biosphere. UKI the virus – propagated – transmits, infects and mobilises the citizens to enter the occupied human body – to infiltrate BioNet, to sabotage the ORGANISMO production and finally to reclaim lost orgasm data.

UKI is a [science] fiction that takes into account the current advancement in biotechnology and mobile digital living. The insertion of microchip implant beneath the skin for body-data-tracking purposes has opened up our bodies for occupation. The integrated circuit transmits personal bio-info to the BIG DATA which we have no access to. Welcome to the era of BioNet, a corporate scheme to own your data, to own you. To certify our very existence these days, we are willingly uploading our personal data to all sorts of social network platforms. The sensors embedded in the smartphones identify our geo-location, track our body movement, guide us to navigate across borders. Drifting spaces, we have been integrated as a mobile device.

I.K.U. takes influences from Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep which was made into Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. What other works have influenced you?

I am very much engaged with Samuel R. Delany’s work, science fiction (Babel-17, Nova, Dhalgren, and the Return to Nevèrÿon series) and his extreme writing on sexuality, Hogg and the Mad Man. I have collaborated with Pat Cadigan (Synners). UKI takes its references from Greg Bear’s Blood Music (1985).

How do you position your work in the wider science fiction canon, which is predominantly white, cisgendered, and heterosexual?

Technology on loan, life on the edge, somehow I squeeze myself into the [science] Fiction, in step with personal/social/political self-development.

As the [science] fiction goes…

The electric sheep are set free range;

the obsolete humanoids are dumped on the e-trashscape;

the coin locker baby takes a teacup ride;

the human bodies held hostage set for the BioNet startup;

the erythrocytes programmed learn to compute orgasm data;

the Net composted bursts fresh sprouts;

the seeds gone underground leaving farmlands barren;

agliomania charges the air;

garlic is the preferred stinky currency;

liquid future packaged are made to order;

hoodies patched are made to network;

Paris declares AIDS free by year 2015;

the HIV virus mutated prompts sexual high;

enter the BioNet

I hear the blood running.

[1] I refer to an article Ruby Rich wrote, The I.K.U. Experience, The Shu-Lea Cheang Phenomenon, written for I.K.U. Sundance Film festival screening and later included in her book New Queer Cinema. It was recently republished at rhizome.org.