I am searching for swans online.

I am searching for swans online.

This means: a) searching for information about swans, b) searching for images of swans, c) searching for swans to buy.

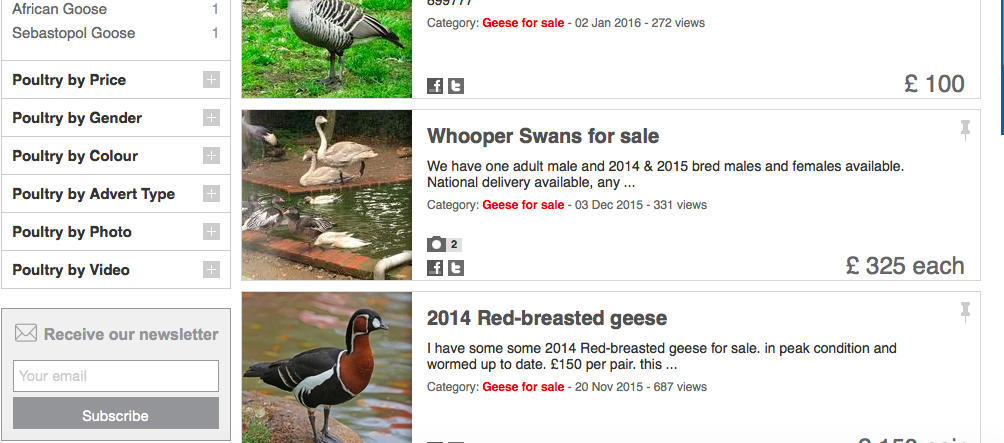

To buy a swan first go to birdtrader.co.uk then click on ‘Poultry’ then click on ‘Geese’ then scroll down and, if you’re lucky, you might find a swan or two amongst the Barnacle Geese and Canada Geese and Grey Lags. Input credit card details, delivery address, postage and packaging, etc.

I didn’t get far enough to discover the latter stages of this process for myself. I just imagined them. And I am imagining, too, the swan arriving at the office in a wooden box, lined with straw, an attached invoice and receipt, a warranty, Terms and Conditions, a booklet of instructions. We would get a call from reception. “Swan here,” he would say.

Swans do not have a webpage of their own. For the purposes of online bird trading they are categorised as geese. They are devoid of a discrete online identity; they have no avatar nor username/password.

I discuss with my colleague, M, the ethics of buying a goose (did I say goose, I meant a swan!) online and putting it in an exhibition space.

Still living, of course. There would be nothing untoward.

Her first concern was that the swan would get lonely. This is an interesting, touching, moving first concern and demonstrates a high level of emotional intelligence. My first concern was that the swan would assault us, violently, for everyone knows that, when provoked, swans break human bones. This is a different sort of concern.

To combat swan loneliness, two swans can be purchased instead of one. Swans choose a mate and remain with that mate for life. Everyone is also aware of this swan-fact. It is common knowledge in the knowledge-category, “Swans.”

We could buy a bonded pair of swans from birdtrader.co.uk and install them in the exhibition space. They would not get lonely but perhaps their feet would be uncomfortably dry. There are no large expanses of water in the gallery for swan-swimming or webbed toe-dipping.

We could get an inflatable paddling pool, like those bought by the parents of toddlers, in which the toddlers learn to float. We could get one of those and put it in the exhibition space, and soon enough the bonded pair of swans from birdtrader.co.uk would be zipping around and around on the inflated, synthetic pond.

In the Middle English romance Cheuelere Assigne the remaining swan is suddenly so lonely he pecks at his own chest until it bleeds. He has been left alone. The sole swan. And his brothers and sister, now human, walk away to join their human mother and father and the assembled crowd, leaving their swan-sibling behind, pecking and bleeding.

I am sorry. Now I have spoilt the ending of the Middle English romance Cheuelere Assigne. Forever.

On this side of the Auto Italia building we have the aforementioned pigeons. On the other side of the building there is a flock of parakeets, as there are all across London now. Their parents or grandparents or great-grandparents escaped from cages and made a go of it. I can hear them when I stand in the kitchen and wash the coffee cups. They whistle and hoot; they click and cluck.

I am keenly aware, however, that a short walk down the road is a shop selling all sorts of plastic-electric goods. It sells knock-off Playstation controllers and iPhone chargers and flashing lightsabers. Hanging above the door are several plastic birdcages. They are based on those old, wire, domed cages you can still find in antique shops or in home-wear shops that contain replicas of antiques. Each of the plastic birdcages is home to a plastic parakeet. And they whistle. And they hoot. And they click and they cluck.

And in all honesty they fool me every time. What with the chug of heavy traffic along Bethnal Green Road, and the hub-bub from the market, and the conflicting melodies from the PA systems of neighbouring shops, and what with the fact that I have never really been able to distinguish certain sounds with any real accuracy, I hear the tweet and I think parakeet.

We swiftly decide not to buy real, live swans off the internet to put in our installation. Instead we will find something swan-like. Something that looks like a swan or sounds like a swan. Or something that neither looks nor sounds like a swan but which is, nevertheless, like a swan in other respects.

A litter of seven babies are born to the queen of Lyon with silver chains around their necks. A mother-in-law conspires to have them killed. They are taken to a dark forest, of the sort that no longer exist in Europe, and there they are left. Wild animals live in forests. Hermits live in forests all alone, and, surrounded by the wild animals, they become to them what dogs are to us. Domesticated. Sylvanised. A hermit finds the seven babies with silver chains around their necks and raises them as his own. They are suckled by a hind. There they remain. Seven years later the mother-in-law discovers her grandchildren are still alive and sends a forester to kill them. He rips the silver chains from the necks of six of the children, they become swans and fly away.

It is difficult, I have always found, to write about medieval literature without adopting a faux-Victorian tone. Others seem to manage just fine, but my pronouns and prepositions become garbled. To the ends of sentences my verbs creep. There they are left. There they remain. Medievals did not speak like Victorians and they did not think like Victorians and this inclination might have something to do with screens. And with the way well-trained British actors come to speak when they are imagining themselves as venerable figures of the past. But also, largely, it might be because of the way Victorians revived and edited medieval stories. These collectors and commenters seem ever- present.

The forester takes the silver chains to the mother-in-law and claims to have slain the children. She commissions a smith to transform the chains into a cup. When the smith is able to make a whole cup from just a small part of one of the chains, he realises that they are enchanted and he secretly keeps the remaining five chains for himself.

All the while the children are living, far away, as swans. An angel comes to the hermit and tells him of their fate and instructs him to christen the remaining brother Enyas and send him to the court of the king and queen of Lyon, his father and mother. The mother-in-law has convinced her son to burn his wife at the stake (the birth of seven children all at once must indicate that she had sex with their dog). Enyas fights to save his mother – though before doing so he asks the hermit ‘What is a mother?’ – and he throws the mother-in-law, whose name is Matabryne, his grandmother, onto the pyre in her place.

The six swan-children return and five of them are given back their chains and become humans again. The sixth swan, whose chain the smith broke to make the cup, remains a swan.

But on was alwaye a swanne for losse of his cheyne

Hit was doole for to se þe sorowe þat he made

He bote hym self wth his bylle þat all his breste bledde

And alle his feyre federes fomede vpon blode

And alle formerknes þe watur þer þe swanne swymethe

There was ryche ne pore þat myȝte for rewthe

Lengere loke on hym but to þe courte wenden