A History of Two Mountains is a group exhibition that takes the traditional format of the blockbuster summer show. It brings together well-known contemporary artworks, such as Felix Gonzalez Torres’ candy spill, with the less familiar, like an early piece by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster.

The thirteen artworks exhibited in this exhibition have been re-made, totally independently of the artists to whom they are attributed. Although they are copies, all the works have been carefully chosen so that when they are duplicated, the copy becomes as valid as the original.

For example, to re-create Liam Gillick’s The hopes and dreams of the workers as they wandered home from the bar, red glitter has been scattered on the gallery floor. For Martin Creed’s famous 227: The lights going on and off, a lamp has been fitted with a timer switch, so that it does indeed go on and off.

The title of the exhibition, itself borrowed from a song by Lawrence Weiner, summarises the tone set by the show: ‘One the original, two a copy, both equally heavy.’ A straightforward copy can end up as a pale imitation of the original, but, for example, the Richard Prince photograph has been re-created by returning to the artist’s own source material. Prince re-photographed images of cowboys found in Marlborough magazine adverts, so the Richard Prince work in this exhibition is an image taken directly from Marlborough advert.

Some of the works in the exhibition have been re-made by the artists themselves, re-configured for each location they are exhibited in. Daniel Buren’s endlessly repeated formula of 8.7 cm-wide vertical stripes is repeated here once more, occupying a door leading out of the exhibition space. This is accompanied by a piece from Philippe Parreno: a door handle made from a Christmas bauble, originally part of his exhibition Snow Dancing at Le Consortium in Dijon, a work which was later ‘recycled’ for the group show Utopia Station at the 2003 Venice Biennale, and is re-used again here.

In other cases, artwork can travel to an exhibition venue as a set of instructions to be realised by technicians on-site and not by the artists themselves. The Ann Veronica Janssens’ work has been re-created using the materials specified by the artist, and the Andreas Slominski’s melted ice lollies on the floor are just that, melted ice lollies, on the floor. Perhaps the work that is most likely to have been faked by accident.

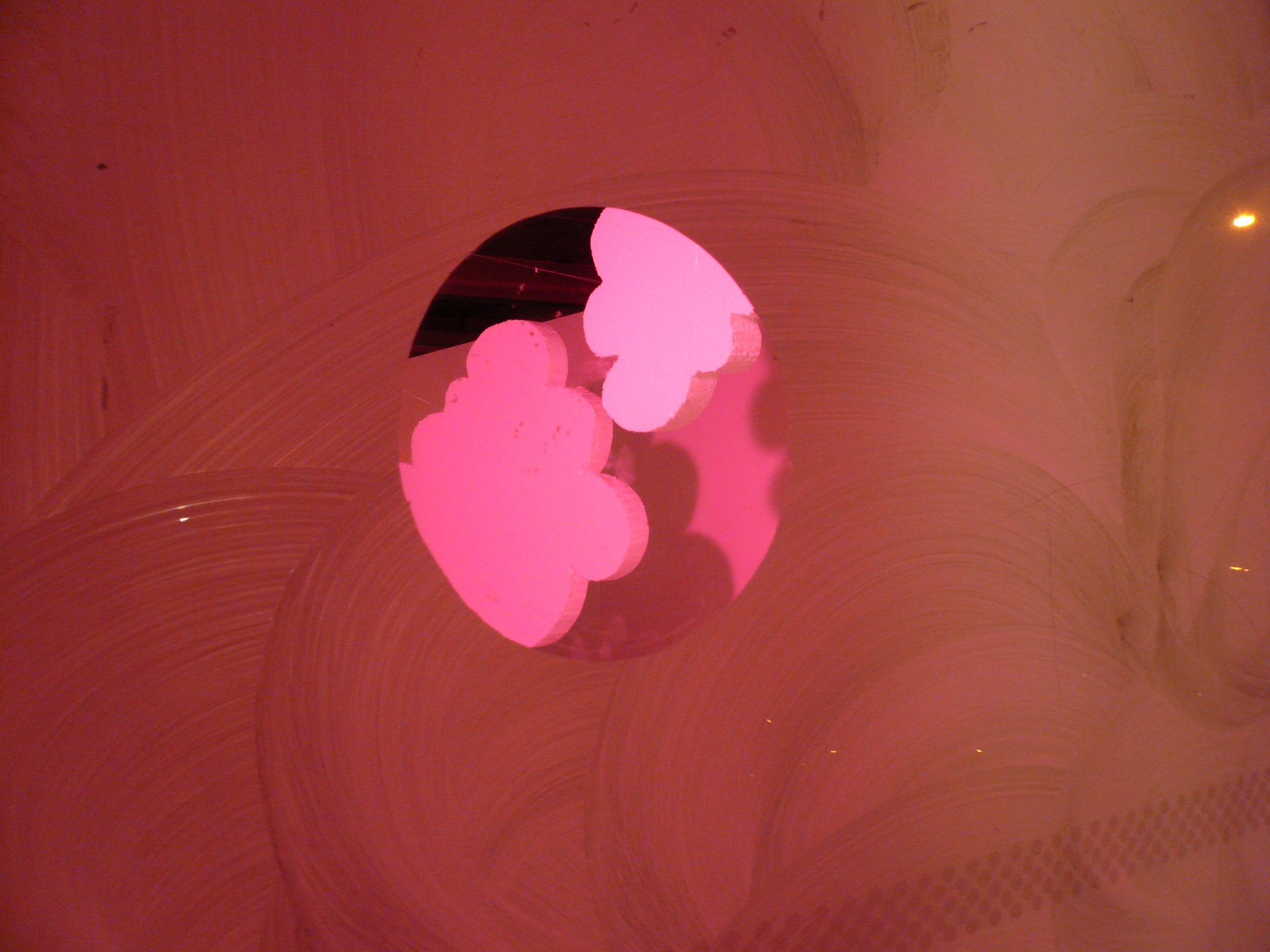

But not all of the works are devoid of the hand of the absent artist. In both Le Rayon Vert by Fischli & Weiss and the suspended polystyrene clouds by Urs Fischer, the element of craft is clearly visible. However, this is not intended to demonstrate high levels of skill and proficiency. Instead the works look homemade, with visible marker pen lines around the rough edges of the clouds, and cardboard and masking tape forming the main components of the base for the rotating plastic cup.

A History of Two Mountains could be read as a critical statement designed to undermine the value of works that are so easily duplicated, but it should also be seen as a less cynical attempt to recreate beautiful and amazing artworks, simply for the pleasure of seeing them.